It’s a sweet treat to watch the soft-spoken and diminutive Marie Kondo arrive at one cluttered home after another, inspiring order from chaos on her new Netflix show, Tidying Up with Marie Kondo. Kondo’s two books have been around for several years. Her New York Times best seller The Life-Changing Magic of Tidying Up: The Japanese Art of Decluttering and Organizing first appeared in 2014 followed by her more recent work, Spark Joy, in 2016. But it is the Netflix series that appears to be bringing Kondo’s KonMari method for managing messy homes back into the spotlight.

In the meantime, in another corner of the planet—Sweden, that is, artist Margareta Magnusson shares her experience with dostadning, a word that combines the ideas of death and cleaning. Magnusson’s book, The Gentle Art of Swedish Death Cleaning, published in 2017, also targets the perplexing question shared by a growing number of the earth’s inhabitants: what do we do with all of our stuff? Compared with Kondo’s approach, Magnusson’s theme borders on the morbid as well as the practical. She suggests it’s our responsibility to declutter and simplify our lives to prepare for death. “While one would usually say ‘clean up after yourself,’ here we are dealing the odd situation of cleaning up before . . . we die,” she writes. “Some people can’t wrap their heads around death. And these people leave a mess after them. Did they think we are immortal?” she asks (9).

I confess I haven’t read either of Kondo’s books—only binge-watched Season One of her show. I intended to read Kondo’s first book when I ran across reviews for it searching for information about Alan Durning, another intriguing writer with his warnings about the looming consequences our mindless acquiring of stuff will someday have. Durning’s essays and book How Much is Enough? The Consumer Society and the Future of the Earth (1992) certainly haven’t garnered the attention of Kondo or Magnusson’s work, maybe because of his rather frightening but inevitable truthfulness.

Magnusson’s Relevance to Our Generation

However, I have taken the time to read Magnusson’s book, and it speaks to the 60-year-old me with far more relevance than Kondo’s cheerful “tutoring” on Netflix or Durning’s dire warnings. In fact, Magnusson’s line of thinking parallels that of Durning as she writes, “This cycle of consumption we are all part of will eventually destroy our planet – – but it doesn’t have to destroy the relationship you have with whomever you leave behind” (33).

The value in Kondo’s work seems to lie in bringing order to the hectic lives of families and in turn, more mindfulness as they accumulate new things. Magnusson, on the other hand, serves as a stalwart guide to eliminating our massive accumulation of possessions before they become a burden on our children.

Bearing the Burden of our Parents’ Stuff

Magnusson’s message hits home for my husband and me. As children and grandchildren ourselves, we have been involved in the emotional task of dealing with the “heirlooms” from our parents’ and grandparents’ closets and cupboards and their boxes upon boxes of mementos. Unfortunately, as the oldest son and daughter, much of this stuff is now in our basement because our parents and grandparents brought it to us with each visit, little by little, as their lives were winding down. We were annoyed at the time, but as I have read Magnusson’s book, it occurred to me they—mostly our mothers– must have reached some pinnacle themselves about their own mortality. When we have taken a moment to dig through the boxes and tubs, we’ve found their notes attached to some of the items—”Great-great grandmother O—‘s engagement ring,” “Great-grandfather J—‘s shaving cup,” and “Grandmother W—‘s baby shoes.”

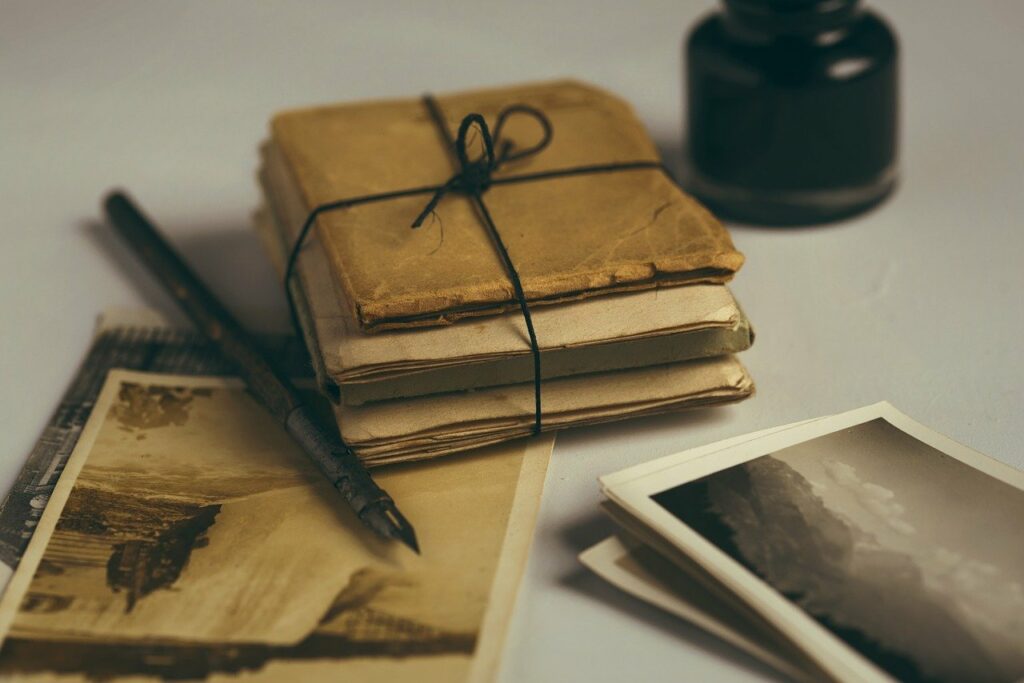

In our recent move, we attempted to sort through these things, but barely knew where to begin. And so these boxes and tubs followed us to our new home and now fill up a large corner of our basement–letters dating back to the 1830s, books older than that, photos as old as photography itself, china and relish plates, egg cups and silverware, handkerchiefs and hatpins, quilt tops and coverlets, music boxes and teapots, old Bibles and funeral flags, a lasso and hunting calls made from mountain goat horns. There is even a box of delicate pantaloons and bodices worn (and patched) by my great-grandmother . . . and so much more from the 40 years my husband and I have shared together ourselves.

Enjoying the Present Requires Letting Go of the Past

Magnusson, who professes to be “between 80 and 100,” writes with a seasoned voice as she discusses the need to rid our homes of the unnecessary things that only complicate our lives as we grow older. She suggests these things keep us in the past rather than allowing us to move forward and enjoy the present. As I moved through the pages of the book, this message makes sense, although I haven’t yet reached the point that I feel our well-being is compromised because we choose to hold on to so many possessions with emotional ties. However, when I remember the tremendous chore involved in helping to close down the households of my husband’s parents and mine, I know decisions must be made. We want to ensure our children don’t experience the same inconvenience, wasting valuable time in their busy lives cleaning up after us and even having moments of resentment toward us. Our children are the ones who will eventually be affected because we can’t let go of the past.

Magnusson’s Process for Letting Go

Magnusson’s process of letting go is similar to Marie Kondo’s KonMari method which suggests we rid ourselves of clothing first, followed by books, papers, miscellany, and finally mementos. Magnusson also advises readers to start with the big stuff first: “Pictures and letters that you have saved for some reason must wait until you have arranged the destinies for your furniture and other belongings,” she notes (15).

And, whereas Marie Kondo advises us to determine an item’s value by whether it sparks joy for us, Magnusson asks us to consider whether the item will bring joy to someone else after we are gone. She writes,”The more I have focused on my cleaning, the braver I have become. I often ask myself, Will anyone I know be happier if I save this? If after a moment of reflection I can honestly say no, then it goes into the hungry shredder, always waiting for more paper to chew. But before it goes into the shredder, I have had a moment to reflect on the event or feeling, good or bad, and to know that it has been a part of my story and my life” (61).

Death Cleansing Begins Long Before Death

The author offers a number of suggestions for ridding ourselves of our treasures in ways that will have meaning for us and those with whom we share the process. First, she emphasizes that we start early so that the process is carried out thoughtfully and the things that have the most value for us end up with others who will value them most; she suggests 65 is an appropriate age to begin although, she notes, unexpected death can come at anytime and the suggestions she provides are applicable to younger adults as well as old. In fact, she devotes a page to the children of elderly parents, advising them to find a gentle way to talk with their parents about starting the process of death cleansing if they haven’t already done so. “If you are too scared to be a little “impolite” with your parents and you do not dare to raise the topic or ask them questions to help them think about how they want to handle their things, don’t be surprised if you get stuck with it all later on!” she explains. “A loved one wishes to inherit nice things from you. Not all things from you” (25).

In addition to putting bundles together with individual family members in mind or inviting them to choose items that have special meaning to them, Magnusson notes the joy she has found in locating other sources who might be interested in her things. “While death cleaning I have gotten to know some interesting, funny, and nice people when I have contacted auctioneers, antiques dealers, secondhand shops, and charity organizations” (29). And, the author explains that she no longer purchases flowers or hostess gifts when she is invited to someone’s home. She gives that person one of her treasures instead, something she knows will have value to him or her.

Create Relevance with Narrative

In addition, Magnusson states that the recipients of our things don’t have to be family members. There are many young people setting up housekeeping for the first time who might welcome our furniture or kitchen gadgets. Then, they in turn might pass these things on to someone else as they gradually afford to replace them with new items. She also adds it is important to share the story behind an item so that it has relevance for those who receive it. She offers, for example, stories about various people who owned a 300-year-old desk and the many letters written on it with quill and ink.

Magnusson Inspires Us to Rise Above Sentiment

Much of Magnusson’s book is more of a pleasant conversation than a focused step-by-step approach to purging and pitching. She ponders letting go of everything from her children’s hand sewn clothes, to her husband’s tools, and even carefully guarded family secrets. “While we seem to live in a culture where everyone thinks they have the right to every secret, I do not agree” she explains. “If you think the secret will cause your loved ones harm or unhappiness, then make sure to destroy [it]. Make a bonfire or shove them into the hungry shredder” (41).

With the exception of the emotion in her chapter about letting go of pets, Magnusson’s lack of sentimentality gives me courage, although I have not reached the tipping point yet. I nor my husband can summon the nerve to part with many items in our possession that once belonged to our parents or our grandparents and have no value, no memories, no meaning for anyone but us —recipes written in my grandmother’s hand, old books with notes in the margin, a serving spoon, binoculars in a leather case, a table cloth, a weather gauge . . . But, Magnusson is rallying my nerve, as she writes–“now is not the time to get stuck in memories. No, now planning for your future is much more important. Look forward to a much easier and calmer life–you will love it!” (29).

So, what about you? Why is it so difficult to get rid of material possessions? What gives them value? What is the tipping point for in which a person becomes a hoarder?

Magnusson, Margareta. The Gentle Art of Swedish Death Cleaning. Scribner, 2017.

And a special thanks to Stillworksimagery at Pixabay for the image.